Hum Fay

Butte over the years had a contradictory relationship with its Chinese citizens.

During one mayoral race, William Owsley won with the slogan “Down with Chinese cheap labor.” The Butte Miner newspaper concluded in an editorial that “a Chinaman could no more become an American citizen than could a coyote.” Meanwhile, one local Chinese man, Jimmy July, was well respected and became a naturalized citizen. In 1896, Jimmy July was the star of the Fourth of July celebration, reciting the Declaration of Independence from start to finish.

Even as many Chinese studied to become part of America’s “melting pot” other recent immigrants from other countries rallied to discourage their assimilation.

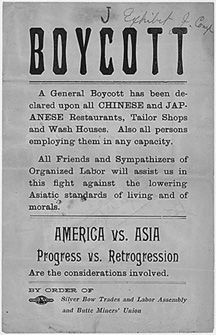

Organized efforts to evict the Butte Chinese were mounted in the 1880s and the 1890s. As early as 1884 a circular was posted ordering the Chinese to leave Butte. In the winter of 1891-1892, a boycott failed due to lack of public support.

When a more aggressive boycott followed in 1896, rather than leave, a group of Butte Chinese led by Hum Fay, Quon Loy, and Dr. Huie Pock decided to fight back against the boycott. They protested to the governments of China and the United States and filed suit against the leaders of the boycott. A copy of the affadavit signed by Hum Fay and filed against the boycott in Butte is now kept in the National Archives.

They won their case and got an injunction to end the boycott, but they were unable to collect damages, which they estimated to be about $500,000 dollars in lost business between 1886 and 1901. While they were reimbursed $1,750.05 for their legal fees and expenses, about 350 Chinese left Butte as a result of the boycott.

In the 1880s, violent anti-Chinese riots erupted in many cities in the West, including Denver, Seattle, Tacoma, Los Angeles, and Rock Springs, Wyoming, but not in Butte. If there is any positive thing about the effort to drive a minority from its midst, it is that there were no incidents of mob violence in Butte as elsewhere in the Northwest during this wave of anti-Chinese violence.

After the Butte Chinese won their injunction against the boycott, they settled into an uneasy peace with the larger community for the next two decades, the time that corresponds with Butte’s greatest prosperity.

The relative truce after 1901 with the larger community did not translate into tranquility, however. During this time, the Chinese had issues to settle among themselves. For details, see Tong Wars.

By 1906, public opinion toward the Chinese as reflected in the local papers had mellowed considerably. In a May 20, 1906 story about Chinatown in the Anaconda Standard, this is how the reporter characterized the Chinese:

“They care for their own people and don’t burden welfare, they never bring suit in court and are never sued. They are fast becoming Americanized and the mission in Chinatown is Christianizing many of them. Society people in Butte have made the Chinese noodle parlors popular places to eat and Chinese truck gardens on the flat provide the city with fresh produce. They measure up well to other foreign groups in town and are definitely more peaceful.”

By 1910, Butte, Montana thrived as an industrial metropolis of from 60,000 to 100,000 with a thriving Chinatown of 400 to 600 Chinese according to Montana historian Dr. Michael Malone. That number may be low, too, based on inaccurate census statistics that didn’t reflect the true population for a variety of reasons. According to Rose Hum Lee in The Chinese in the United States of America, from 1870 to 1910 the Chinese population varied from 1,265 to 2,532 inhabitants. From 1895 until the 1930s, Asian entrepreneurs operated dozens of different businesses in Butte. The 1914 Butte city directory lists 62 Chinese businesses, including four physicians who practiced herbal medicine. One of the most prominent men among businessmen in Butte’s Chinatown was Hum Fay of Sun Ning, Canton.

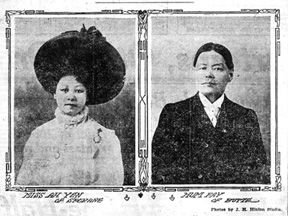

In a 1909 newspaper article about his Butte wedding to the American-born Chew Gum of Spokane, Washington, a reporter for the January 17, 1909 edition of the Anaconda Standard wrote:

In a 1909 newspaper article about his Butte wedding to the American-born Chew Gum of Spokane, Washington, a reporter for the January 17, 1909 edition of the Anaconda Standard wrote:

“Although confessing 38 years, Hum appears not more than 30. He is a handsome Chinaman, having cultivated all the refinement of an educated American, quiet in manner, deferential alike to friend or stranger, keen in business, respected by all classes, and the possessor of considerable wealth.”

That wedding caused a stir because it was so rare for a Chinese man to marry. A Chinese Baptist Mission ministered to the Christian population within Chinatown. Many of Butte’s Chinese were Protestant Christians, Baptists not Buddhists. The fastest path to assimilation was through the Baptist Mission where Chinese children and adults learned English and the mysterious ways of the larger community. Hum Fay’s wedding was ministered by Rev. J.E. Noftsinger of the First Baptist Church.